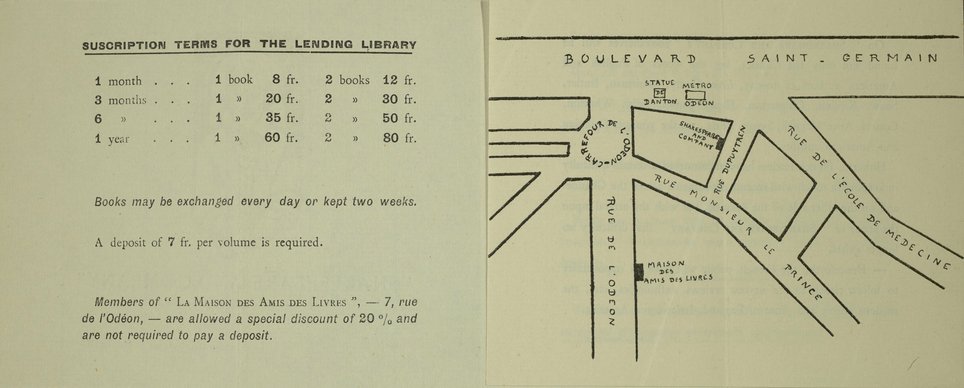

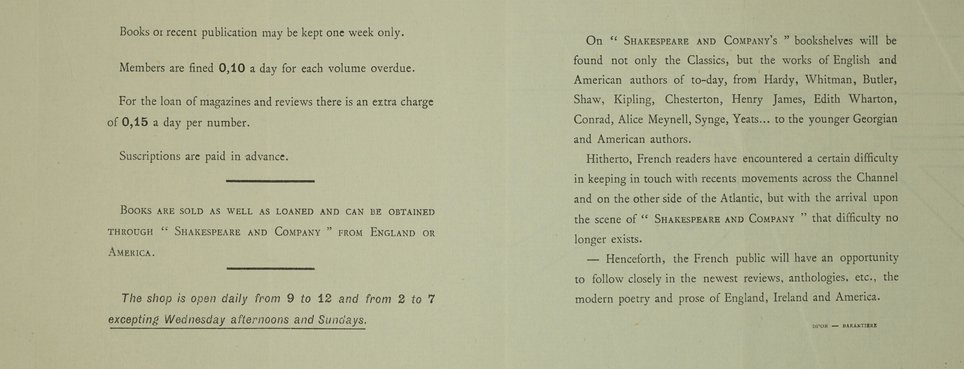

It’s 1920. You’ve just moved to Paris—to work, to study, to escape. You want to read English-language books. What are your options? You could buy books at Brentano’s, a bookshop at 27 avenue de l’Opéra on the Right Bank. But English-language books are expensive—five to twenty times the price of French books. You could join the American Library in Paris, another Right Bank institution, at 10 rue de l’Elysée. But the holdings are limited—based on a collection donated by American libraries during the War. Luckily, you’ve received a flyer for Shakespeare and Company, a new bookshop and lending library at 8 rue Dupuytren on the Left Bank. The flyer even includes a map. You decide to visit.1

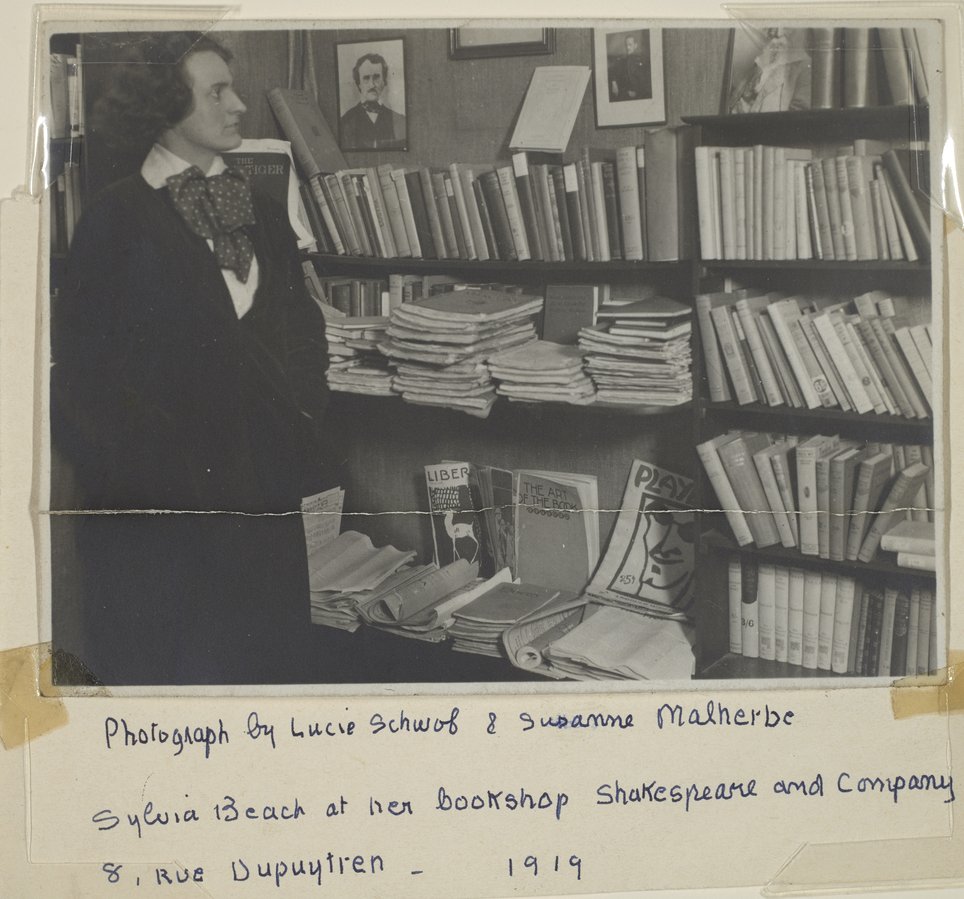

You find Shakespeare and Company on a narrow side street, just off the Carrefour de l’Odéon. You step inside. The room is filled with books and magazines. You recognize a framed portrait of Edgar Allan Poe. You also recognize a few framed Whitman manuscripts. Sylvia Beach, the owner, introduces herself and tells you that her aunt visited Whitman in Camden, New Jersey and saved the manuscripts from the wastebasket. Yes, this is the place for you.2

You ask to join the lending library. Sylvia outlines the terms. For eight francs plus a seven franc deposit, you can join for a month and borrow one book at a time. For twelve francs and a fourteen franc deposit, you can borrow two books at a time. You are allowed to keep older books for up to two weeks, recent books for one. You’ll be fined ten centime-a-day for overdue books. If you’re a member of Adrienne Monnier’s La Maison des Amis des Livres, a French bookshop and lending library at 7 rue de l’Odéon, no deposit is required and you’ll receive a twenty percent discount. You decide to join for one month, one book at a time and give Sylvia fifteen francs. She promises to return the deposit when you cancel your membership.

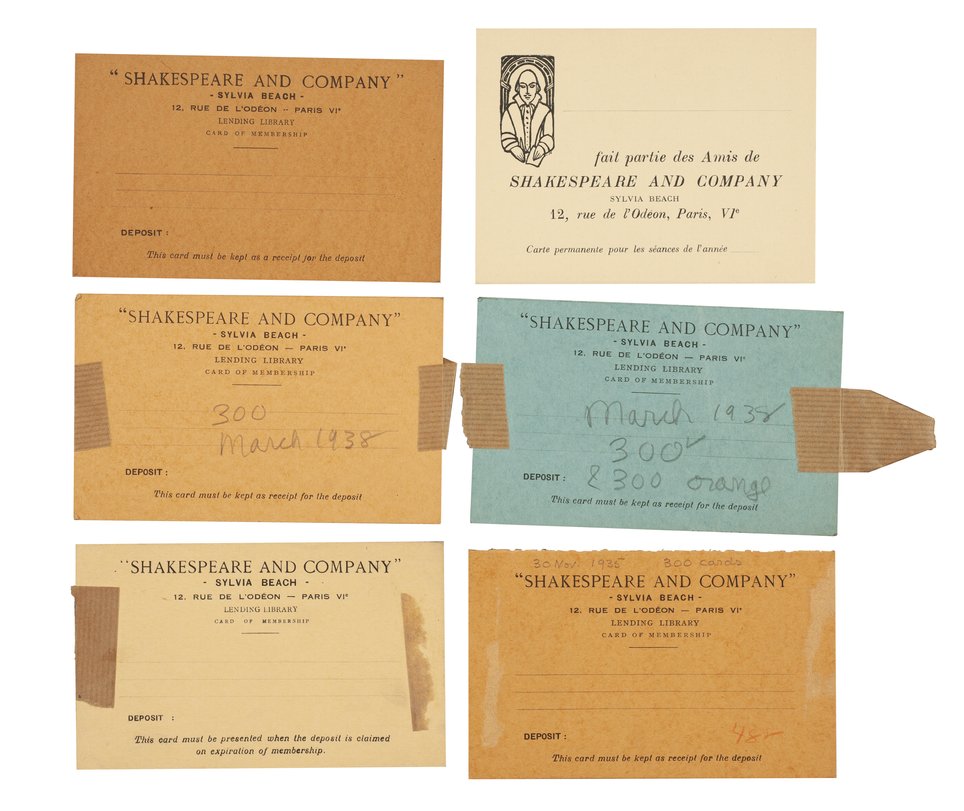

Sylvia hands you membership card and creates a lending library card to keep track of your borrowing activities. She also notes your membership and payment in a logbook. You begin to browse the shelves. You look at recent magazines—The New Republic and The Dial, Poetry and Playboy. You ask about Virginia Woolf’s recent novel, Night and Day (1919). It’s out, but Sylvia suggests checking back later in the week. You consider Ezra Pound’s collection of essays, Pavannes and Divisions (1918), and Upton Sinclair’s muck-racking The Brass Check (1919). You also consider, somewhat guiltily, Andrew Soutar’s Equality Island (1919). (You’re relieved that Shakespeare and Company has fantasy novels.) But then you see a thin volume with a colorful cover: Woolf’s Kew Gardens (1919), recently published in a limited edition by Hogarth Press with woodcuts by Vanessa Bell. You bring it to Sylvia, who seems to approve. She notes the title on your lending library card and reminds you to return the book by the end of the week. You promise to be back in a day or two. At your next visit you might meet Gertrude Stein or Valery Larbaud or Claude Cahun.

It’s now 1927. You’ve decided to move back to the United States. Paris is overrun by Americans. Parisians are giving you angry looks in response to developments in the Sacco and Vanzetti case. You drop by Shakespeare and Company and give Sylvia your membership card. She returns your deposit and notes it in a logbook. You wonder if she’ll keep your lending library cards. You decide to buy four copies of James Joyce’s Ulysses, which is now in its eighth printing, to smuggle home for friends and to keep as a souvenir for yourself. (The book would be banned in the United States until 1934.)

This is how the Shakespeare and Company worked. In 1921, the bookshop and lending library moved to 12 rue de l’Odéon, across the street from La Maison des Amis des Livres. By that time, Beach and Monnier were living together as lovers. In 1922, Beach published Ulysses under the Shakespeare and Company imprint. In January 1926, the lending library membership reached its peak with 230 active members.3

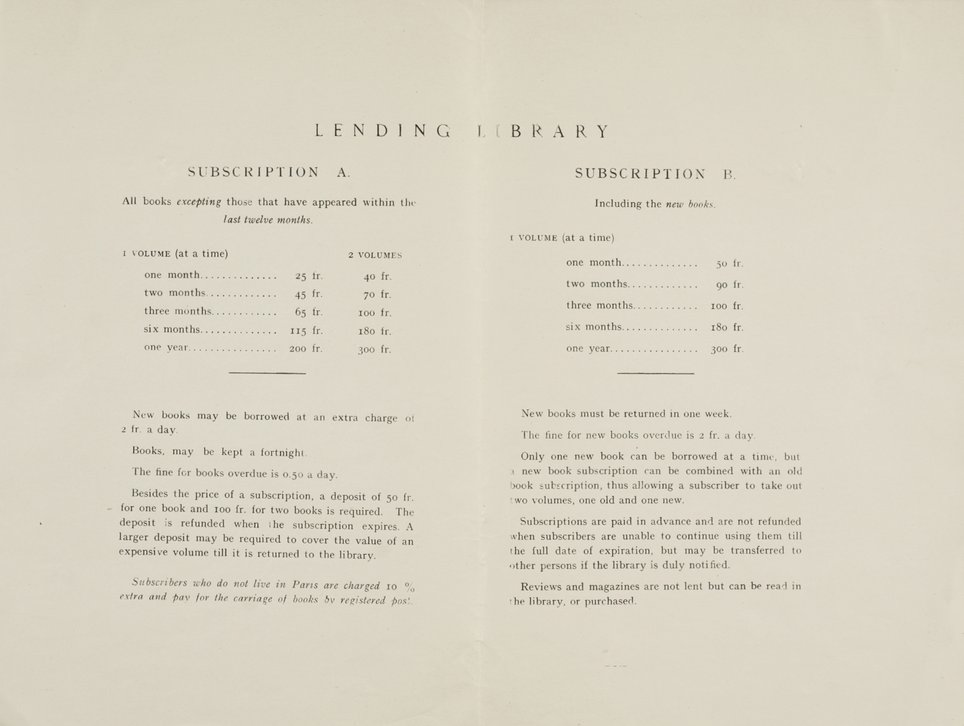

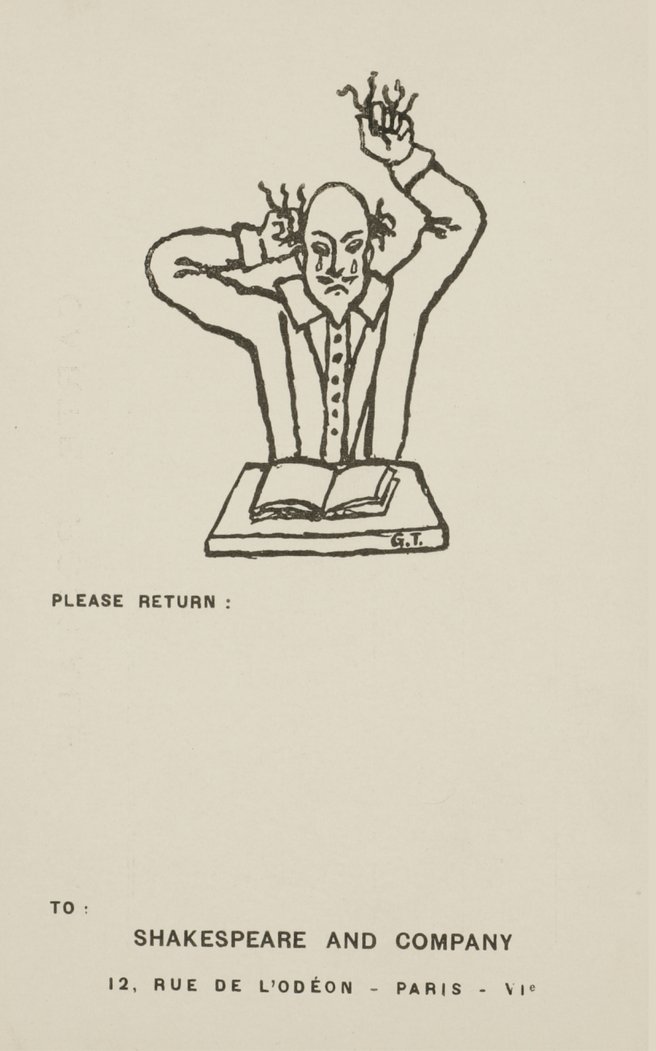

Over the next twenty years, Beach would issue new flyers and promotional materials, often employing Maurice Darantiere, the printer of Ulysses. Rates increased as did the membership options. Beach introduced student discounts, extra charges for members who lived outside Paris, and day-by-day borrowing rates. Eventually, she offered two membership categories, “Subscription A” and “Subscription B”: one for “All books excepting those that appeared within the last twelve months” and one that included “the new books.” She would also send overdue notices, featuring a drawing of an exasperated Shakespeare pulling out his hair. Shakespeare and Company closed in 1941. But Beach continued to loan books to friends until her death in 1962.

1. Sisley Huddleston, Paris Salons, Cafés, Studios (Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1928), 208; American Library in Paris, “Lending since 1920,” https://americanlibraryinparis.org/history/, accessed 8 November 2019.

2. Noel Riley Fitch, Sylvia Beach and the Lost Generation: A History of Literary Paris in the Twenties and Thirties (New York: Norton, 1983), 42–43; Sylvia Beach, Shakespeare and Company (New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1959), 129.

3. Fitch, 73–74.

Cite this document

“Becoming a Member of the Shakespeare and Company Lending Library.” Shakespeare and Company Project, version 1.10.0. Center for Digital Humanities, Princeton University. January 30, 2020. http://shakespeareandco.princeton.edu/analysis/2020/01/joining-shakespeare-and-company-lending-library/. Accessed March 14, 2026.